I often introduce the idea that when you start with a dataset you should first start by asking your data some questions. For instance, in this dataset about food waste in Massachusetts, students in my Data Storytelling Studio course brainstormed a number of questions they wanted ask:

- if there more food waste in rich areas?

- do more expensive restaurants waste more food?

- do restaurants with more waste go out of business at a higher rate?

- are certain towns more wasteful than others?

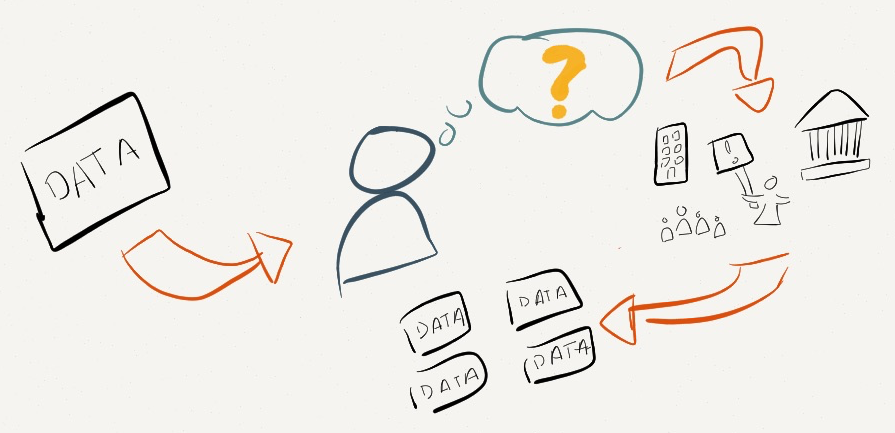

This process of asking questions help you move beyond the data you have, to getting the data you need to answer the questions you have. This question-centric approach is critical to make sure you don’t fall victim to having your dataset in hand be a constraint that stops you from finding an interesting story.

An Example of Getting More Data

So how do you go from these questions to more data? I encourage folks to go “data shopping” (a term I enjoy stealing from my colleagues at the Tactical Technology Collective). This involve taking each of your questions and thinking about what other data you need to answer it, and where you might get that data. Returning to the food waste example above, to answer the question of whether more expensive restaurants waste more food, you need to categorize restaurants as expensive or not. My students remembered that most restaurant review sites, like Yelp, have a dollar-bill scale that tells you how expensive a restaurant is.

How could you get that data? You could do it by hand, but that would take a while for all the restaurants in the food waste spreadsheet. Instead, they pointed out that Yelp has an API, and you could write some software to query that and ask Yelp for the dollar-rating of each restaurant on the list.

Types of Data Sources

This examples uses one source of data – a private company. There are, of course, others. Here’s the list I tend to introduce:

- Private Companies – There is tons of data collected and stored by private companies, and sometimes they will give or sell it to you.

- Governments – There is loads of official data collected by government agencies, and you have a right to the vast majority of it (depending on where you live).

- Non-Profits or Advocacy Groups – Interest groups typically collect datasets to back up and inform the advocacy they are doing.

- Crowdsourcing / Do-It-Yourself – Sometimes the data isn’t there, so you need to make it yourself!

That’s the list I use. Am I missing a category?

Ways to Get Data

Fine, so there is data in a lot of places… how do we get it? Here’s my list of techniques:

- Download Open Data – Yes, sometimes the data is just out there waiting for you to find and download it. This doesn’t mean it is usable, but it is often there. Usually large non-profits and governments have big data repositories you can poke around. Sometimes it will be stuck in a PDF or HTML table, but you can still get it out.

- Ask For It – I mean it. Sometimes you just need to make a phone call and ask. A little social engineering goes a long way!

- Scrape It – Far too often the data is out there, but not in a nicely usable form… you need to scrape it from a website. Scraping involves taking taking data is scattered around a website and using a process to get it all in one place in the same format. Nowadays there are lots of tools to help you scrape websites.

- Manually Collect It – If the data isn’t there, you gotta make it yourself. This might involve crowd-sourced data collection, a focus group, or asking of social media.

Answering Your Questions

I introduce these two lists, of data sources and ways to get data, in order to support the data shopping process. With a richer set of data in hand, you’re better positioned to find the most interested and meaningful stories in your data.

You must be logged in to post a comment.