Here’s video and a writeup of a short 5 minute talk I gave recently at the 2014 Civic Media Conference. I attempt to tease apart my definition of “popular data” by comparing it to the concept of “data literacy”.

Do you “speak data”? As more and more businesses and governments are making data-driven decisions, this question is becoming more important. Your ability to speak data is directly related to your ability to engage with those institutions. For governments this is a critical issue because they are meant to engage the citizenry.

Most folks try to address this, talking about it as “data literacy”, but that doesn’t quite capture the whole idea. The concept of “literacy” suggests a spectrum:

- the illiterate: those that can’t participate in written discussion

- the readers: those that can take in the ideas of others who have written them

- the writers: those who can capture their ideas on paper

The idea of literacy is to move people from illiterate to reading, but the writers are those in control. The writers are those with the power. With data, we need to make more readers for sure. However, the bigger issue is that we can’t just focus on readers when actually we need better writers. This is the piece I see missing from the data literacy work misses.

So who are the existing data writers? Newspapers, community groups, governments, businesses – they all generate data-driven stories for the readers. So how do we make those passive readers into data writers? Well, my studies in the Lifelong Kindergarten Group point me back to Paulo Freire, the Brazilian philosopher and educator.

Freire’s concept of popular education stemmed from his early work on adult literacy, where he focused on learning literary skills by reading local newspapers. The ideas was that the content and context would empower the learners.

There are a few tactics of popular education that are key:

- you must value what each individual brings to the table as a unique and meaningful addition

- the teacher/educator is more of a facilitator for the learners

- thought most be combined directly with action

- the action must be tied to local community needs

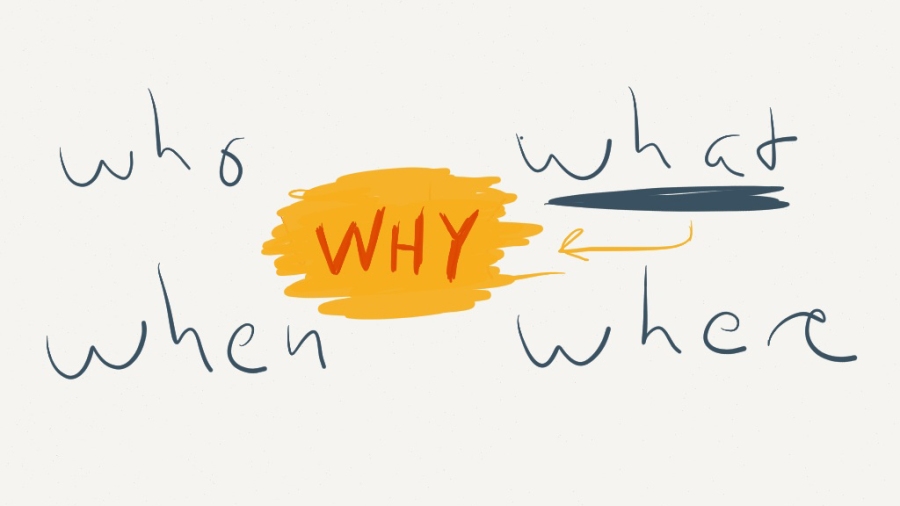

So combine these tenants with the basics of data literacy and you get my new concept of popular data. Whats the difference? Data literacy is about the what. Popular data is about the why.

That’s all really abstract. Lets run through some examples of how this works in the real works.

Newspapers

Newspapers have always played a critical role informing the public. They’ve moved this into the data-driven era by way of things like the Data Driven Journalism Handbook and numerous trainings to help journalists find and tell stories with data. Similarly, they are experimenting with new interactive ways to write exploratory and explanatory data-driven articles.

Governments

Our partners in the state government of Minas Gerais, Brazil realized that an open data portal was the start, not the end, of their open data initiatives. They brought us down to do a series of lectures, workshops, and a data mural that tried to build local capacity to work with that data to advocate for change. This was about turning those readers into writers. I argue governments, as they embrace more data-driven policy, have a moral duty to help their constituency speak data.

Community Groups

These folks could be aptly-described as semi-literate. All Data Therapy workshops aim to build their capacity to present data in more creative and appropriate ways. This is about making them better writers.

Regular Folks

These are the “illiterate”, to a certain extent. To help them become readers and writers, we created the Data Murals project. We want to use the engaging power of the arts to invite them to learn to speak data. This involves creating participatory workshops to engage them when looking at data to find a story, and then collaboratively designing a visual to tell that story, and then paint it as a mural. This is an empowerment effort.

These are some key examples of what popular data means in practice, and why it is important to go beyond the concept of “data literacy”.

You must be logged in to post a comment.